As the climate changes, and our forests are affected, the need to reclaim impacted areas and restore native species becomes more important than ever. The U.S. Forest Service’s Monongahela National Forest is at the forefront of not only forest restoration, but also helping those landscapes adapt to climate change.

The red spruce forests of the Appalachian highlands are an integral part of the regional biodiversity, providing habitat and food for the northern flying squirrel and the Cheat Mountain Salamander, and the ecosystem supports 240 rare species in West Virginia alone. Additionally, the forests blanket the headwaters of five major river systems upstream of millions of people living and working in the Charleston, West Virginia; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Washington D.C. regions.

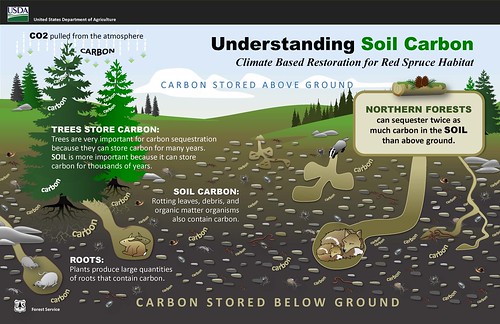

“Different soils have the ability to store different amounts of carbon, and Appalachian soils have potential to store carbon for the long-term if managed correctly. There is evidence of this in the soil profiles under the historic red spruce ecosystem,” said Stephanie Connolly, Forest Soil Scientist on the Monongahela forest.

Most of the soil carbon in the world is found in the cool, moist conifer forests of the north. There is more carbon in the soils than in the atmosphere and the vegetation combined. Historically, timber harvesting of red spruce has resulted in large losses of soil carbon into the atmosphere. Forest Service scientists are helping figure out how to better manage these forests long term to restore lost soil carbon.

The restoration of red spruce to its historic range could restore much of the lost soil carbon within a century, improve wildlife habitat, and protect water resources. In West Virginia alone, recent data suggests that carbon—equivalent to 56.4 million barrels of oil—could be taken out of the atmosphere and incorporated in the forest floor within 80 years.

One example of this work is the work of Monongahela National Forest staff and their partners at The West Virginia Highlands Conservancy and The Nature Conservancy who are working to restore historic red spruce forests on lands that were previously strip-mined for coal. The Lambert Run lands were mined in the 1970s and 1980s resulting in heavy soil compaction and the introduction of non-native plants. While earlier restoration efforts stabilized the land for erosion control, many areas remain in a condition scientist term “arrested succession.”

The partnership uses machinery to break soil compaction and allow water to infiltrate the ground making it healthier to support the native spruce and reestablish critical habitat. Wetlands are being constructed to retain water and support native plant systems. Hardwoods and Norway pine are being removed from the Lambert Run in preparation for the planting of red spruce seedlings.

After this kind of restoration work prepares the soil, the Monongahela forest staff work with climate change specialists to create adaptation management plans to enhance long-term resiliency of the newly restored forests. Together partnerships like this return forested areas into living tools that benefit all of us now and for generations to come.