Today, the work of scientists from the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), our State Land Grant Universities, and the Department of Energy (DOE) is featured as the cover story in the prestigious science journal, Nature. I am very proud and excited that USDA science played an important part in unlocking the genetic secrets of one of the world’s most important crops, the soybean.

Together these scientists have compiled a “blueprint” of all the genetic material contained in the soybean plant. The soybean “blueprint”, which is freely available online, will allow scientists from around the world to locate genes that control and enhance important quality traits in soybeans, like protein and oil, and agronomic traits like yield, drought tolerance, and the plant’s ability to resist pests and diseases.

This blueprint will let plant scientists find genes much faster and speed up development of different and improved types of soybean. With the basic genetic blueprint in hand, the next step will be for scientists to compare the basic design to others, looking for genetic variations associated with particular traits. This is where USDA’s collection of more than 20,000 different types of soybeans will be crucial. Researchers can compare different cultivars to the blueprint, searching for genes associated with desirable traits. Once new genetic associations are identified, scientists can use the information to create better soybeans. Soybeans that can extract more nitrogen from the atmosphere, which means less fertilizer and fewer greenhouse gas emissions. Soybeans with more protein for livestock feed and better nutrition for consumers. Better soy oil for food processors; soybeans with less linolenic acid that doesn’t require hydrogenation, a process which produces unhealthy trans-fats. And even soybeans with more oil designed specifically for biodiesel or biobased applications.

This blueprint will let plant scientists find genes much faster and speed up development of different and improved types of soybean. With the basic genetic blueprint in hand, the next step will be for scientists to compare the basic design to others, looking for genetic variations associated with particular traits. This is where USDA’s collection of more than 20,000 different types of soybeans will be crucial. Researchers can compare different cultivars to the blueprint, searching for genes associated with desirable traits. Once new genetic associations are identified, scientists can use the information to create better soybeans. Soybeans that can extract more nitrogen from the atmosphere, which means less fertilizer and fewer greenhouse gas emissions. Soybeans with more protein for livestock feed and better nutrition for consumers. Better soy oil for food processors; soybeans with less linolenic acid that doesn’t require hydrogenation, a process which produces unhealthy trans-fats. And even soybeans with more oil designed specifically for biodiesel or biobased applications.

An important food crop in Asia for thousands of years, today soybeans are the largest source of protein and the second largest source of vegetable oil in the world so improving soybeans has important implications for food security. Soy products are found in numerous foods including milk and meat substitutes, soy flour, and tofu. Soybeans also have many non-food uses including environment-friendly plastics, inks, lubricants, and solvents.

Although soybeans have only been commercially grown in the U.S. since the 1920s, we are now the world's leading soybean producer and exporter. The U.S. soybean crop has a farm value of about $27 billion, the second-highest value among U.S.-produced crops, second only to corn. Soybeans are also an important export commodity for American farmers accounting for about 43 percent of production in 2008. And while our research on the soybean genome has great potential to improve food security, it will also help keep American farmers competitive.

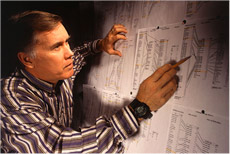

The research to decode the soybean genome is the product of a multiagency, multi-institutional effort led by scientists at the DOE Joint Genome Institute, the University of Missouri-Columbia, USDA, and Purdue University, with additional financial support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Other USDA and university scientists involved include USDA scientists from the ARS Soybean Genomics and Improvement Lab in Beltsville, Maryland, and researchers at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Since the first plant, Arabidopsis thaliana, a small flowering plant in the mustard family, was sequenced in 2000 and the human genome was first sequenced in 2003, scientists have learned a great deal about the role of genes. However, sequencing the genome is but a first step. The genome of an organism is no more than a list of parts. More research is needed to discover the functions and interactions of the genes in order to understand the workings of the entire organism.

The soybean genome project is one of many genome sequencing projects of agriculturally important plants and animals being carried out by USDA and other scientists. Other projects include sequencing corn, rice, wheat, sorghum, cow, pig, sheep, and honeybee genomes. Just this week USDA scientists and others announced they had sequenced the genome of the woodland strawberry, a model system for a group of plants within the Rosaceae family which includes many economically important fruit, nut, ornamental and woody crops, such as almond, apple, peach, cherry, raspberry, strawberry and rose.

The soybean genome project is one of many genome sequencing projects of agriculturally important plants and animals being carried out by USDA and other scientists. Other projects include sequencing corn, rice, wheat, sorghum, cow, pig, sheep, and honeybee genomes. Just this week USDA scientists and others announced they had sequenced the genome of the woodland strawberry, a model system for a group of plants within the Rosaceae family which includes many economically important fruit, nut, ornamental and woody crops, such as almond, apple, peach, cherry, raspberry, strawberry and rose.

Research to understand genomes is a vital investment in our future to ensure our farmers can continue to meet the world’s needs for food, feed, fiber, and bioenergy in the face of climate change, emerging pest and disease threats, and a growing population. The knowledge from this research will translate into new technologies and products that will benefit not only farmers and producers but also people the world over. USDA science will be crucial to our success.

Molly Jahn is USDA's Acting Under Secretary for Research, Education, and Economics