Science can do more than improve people’s lives; sometimes it can save them.

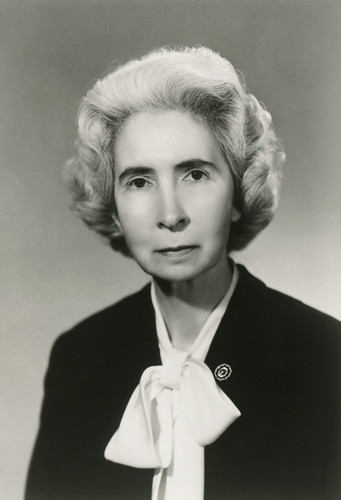

Consider the contributions of the late Allene Rosalind Jeanes, an Agricultural Research Service (ARS) chemist at what is now the National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research in Peoria, Illinois. Her efforts are particularly worth celebrating this Veteran’s Day.

Jeanes studied polymers (large molecules composed of many repeated subunits) found in corn, wheat and wood. She spent long hours investigating how bacteria could produce polymers in huge fermentation vats. Eventually, she found a way to mass produce dextran, a type of polymer, so that it could be used as a blood volume “expander” to sustain accident and trauma victims who have lost massive amounts of blood and need to get to a hospital for a transfusion.

The technology is credited with saving the lives of numerous battle-wounded Americans in Korea and Vietnam, and is one reason why Jeanes, who died in 1995, is still remembered by some of her former colleagues in Peoria.

“She was a very quiet and very distinguished person, and she happened to be a brilliant scientist who saw the potential for what turned out to be critical work. It is an interesting story,” said ARS chemist George Inglett, who was chief of the research laboratory in Peoria where Jeanes spent her later years.

The annals of history are replete with important discoveries sparked by serendipity, and this present story is no different. This particular serendipity involved—of all things—a batch of bad root beer. Jeanes had been interested in dextran for years, but it was hard to find in quantities large enough for meaningful research. That changed when a soft drink company in Peoria sent Jeanes a sample of their product wanting to know why it had become thick and gooey. The root beer turned out to have been contaminated with a type of bacteria that produced dextran. The discovery of the dextran-producing microbes meant Jeanes could produce all the dextran she needed for research.

Meanwhile, researchers in Sweden and England had been investigating the use of dextran as a potential blood volume expander. While it can’t carry oxygen to vital organs as healthy blood cells do, it might, thought the researchers, temporarily help accident and trauma victims suffering massive blood loss by restoring lost electrolytes and maintaining blood pressure.

When the Korean War broke out in 1950, Jeanes and her colleagues were able to make a dextran-based blood volume expander that the Army put to use. The blood volume expander had many advantages: it could be kept longer than blood plasma without refrigeration, it could be sterilized to prevent infections, it was one-third the cost of plasma and it remained viable in the blood long enough to keep patients alive until they could get a transfusion. It was approved for U.S. military use in 1950 and for civilian use in 1953.

Research would later show that dextran wasn’t perfect and the U.S. Government no longer uses dextran as a blood expander. But at a critical juncture in history—and absent viable alternatives—Jeanes’s discovery saved many lives.

Jeanes and her colleagues also discovered xanthan gum, a polysaccharide (or polymeric carbohydrate molecule) synthesized by bacteria that is used to thicken and improve the consistency of ice cream, salad dressings, lotions, cough syrups and many other products. It is also used in the oil and gas industry to extract fossil fuels from the earth.

Jeanes was awarded 10 patents, produced 60 publications and became the first woman to win the USDA’s Distinguished Service Award in 1953. In 1999, she was posthumously inducted into the ARS Science Hall of Fame. She was also awarded the Garvan Medal from the American Chemical Society in 1956 and the Women’s Service Award from the U.S. Civil Service Commission in 1962.

We should all be thankful for the work done by Jeanes and other scientists like her. They’ve not only helped save lives, but they have also made our lives better with new products and technologies.