The Great Lakes cover over 95,000 square miles and contain trillions of gallons of water. These vestiges of the last Ice Age define immense. But their greatness makes water quality monitoring difficult.

In 2010, Titus Seilheimer, a US Forest Service research ecologist at the time, led a project funded by the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative that parsed the vastness of the Great Lakes to estimate water quality in different basins. This information can identify which areas are likely to receive high nutrient inputs – which can cause harmful algae blooms and dead zones – and where resource managers should invest in restoration efforts.

But as Seilheimer said, “We can’t measure water quality everywhere.”

Now, through the US Forest Service’s partnership with ESRI, the work Seilheimer and his colleagues did is presented in an online and interactive story map, one of many produced by the US Forest Service through its continuous effort to develop new and engaging ways to share information.

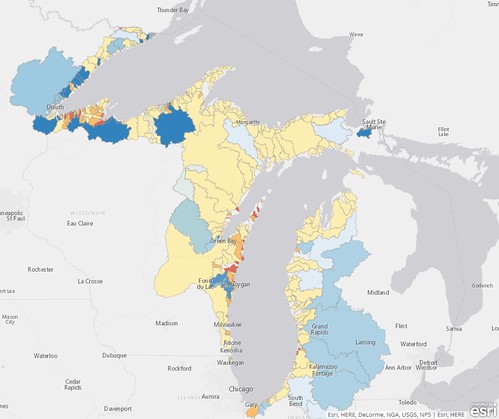

The researchers analyzed satellite imagery for vegetation changes and land use (agriculture, urban, forest, etc.) around Great Lakes basins and watersheds for which water quality data already existed. By doing so they could determine which watershed conditions and land uses result in which downstream water conditions. They applied this cause and effect information to un-monitored basins and watersheds to estimate their water quality based on surrounding land use. These estimates demonstrate how different land uses and changes in forest coverage affect the natural filtering of excessive nutrients or pollutants from water.

“This type of work helps move the needle forward on understanding how the terrestrial environment impacts the watersheds,” said Charles ‘Hobie’ Perry, a US Forest Service research scientist. The story map demonstrates this terrestrial-aquatic linkage and provides maps showing land use, areas at risk for poor water quality, and forest canopy and vegetation changes around the Great Lakes. These tools also share the underlying data with land managers, decision-makers, and other interested users to facilitate their needs.

By using satellite imagery this way the US Forest Service also began to advance its own analysis capabilities. The Great Lakes project led to the development of the Landscape Change Monitoring System, which looks at multiple land cover change algorithms all together – whereas this specific project only utilized one algorithm – to create more detailed analyses of landscapes from satellite imagery.

Projects such as these provide ways to prioritize monitoring and restoration efforts to not only benefit natural ecosystems, but also everyone who lives nearby and relies on them for drinking water, jobs, and recreation.