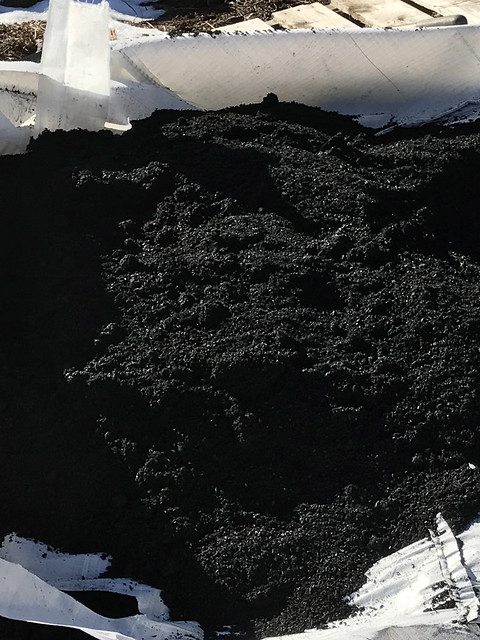

Biochar, or wood waste, is a porous carbon substance that results from burning wood in the absence of oxygen. It is typically created when burning chunks of wood are covered by ash, soil or a lid, which insulates the coals and starves them of oxygen. This fire remnant provides a valuable addition to soil for agriculture and gardening purposes as well as contributing to overall forest health.

When added to soil, biochar increases soil carbon and can restore the soil’s pH balance. Soil with a high carbon content is teeming with life and rich in nutrients, requires less fertilizer and produces healthier food. Carbon-rich soil also absorbs and retains water more efficiently, which helps farmers reduce the effects of floods and drought.

“One thing to keep in mind is that biochar does not add nutrients to the soil, but it can help retain them,” said Forest Service research soil scientist Deborah Page-Dumroese. “Biochar is 80 percent carbon, and that’s the big-ticket item. Adding biochar to soil increases soil’s water-holding capacity, which leads to less runoff and leaching, better infiltration, higher water quality and better downstream water flow because more moisture is retained in the soil.”

Biochar also helps restore soil that has been damaged by fire or human activity. Biochar can be easily made in well-constructed slash piles and be used on-site to restore soil organic matter. In places where this method is used, biochar has extended vegetation growth by nearly a month, resulting in reduced fire risk.

Despite its usefulness, biochar is difficult to produce in large quantities for agricultural, forestry or commercial use. With healthy forests in mind, the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station and Air Burners, Inc. teamed up to optimize biochar production for the marketplace. The company has partnered with the Forest Service through a cooperative agreement to help find a solution to this market problem. The company’s commercial fireboxes, used for processing wood and vegetative waste, are being modified to produce high-quality biochar.

“We’re using non-merchantable forest residues to create biochar,” said Page-Dumroese. “We’ve been testing a forest-to-farm concept in Oregon, where low-value woody biomass, a byproduct of harvest operations, is uniform and abundant. It makes sense that we match the pace and scale of harvest operations to that of biochar production.” Using the Air Burner (and other) production technologies, the Forest Service can help deliver biochar to unirrigated agricultural production markets to extend the economic, social and ecological benefits of our forest restoration efforts.

Applying biochar can even reduce invasive species growth and help native species expand their range. Since many invasive species prefer a nitrogen-rich environment, biochar can reduce invasive species by tying up nitrogen in many soil types. Biochar has also been successfully used in western forests during removal of old roads to restore them to a natural condition and to restore soils after thinning, among other applications.