Have you ever wondered why your favorite National Park is surrounded by a National Forest? Well, it didn’t happen by accident or guesswork. The fact is, it was all started over 100 years ago by two men I like to refer to as the founding fathers of America’s public lands.

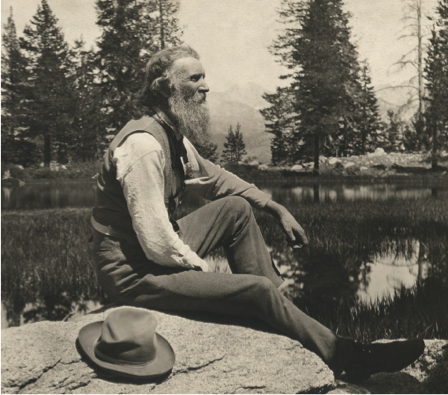

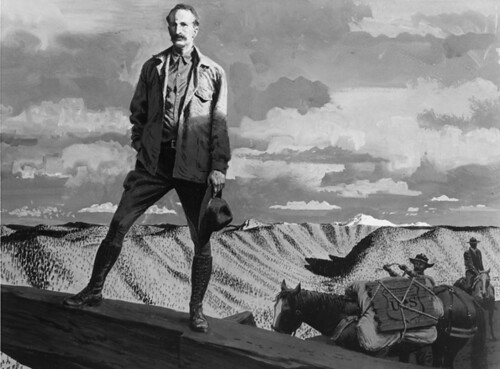

Back at the turn of the 20th Century Gifford Pinchot and John Muir had radically contrasting views of how to manage America’s wild lands and they worked tirelessly lobbying Congress and convincing Presidents to agree with them to start protecting open space.

Muir promoted preservation and Pinchot advocated for conservation.

Pinchot’s vision of managed conservation basically meant that lands owned by the federal government could not only be used for recreation by the general public but could also be used, responsibly, by industry for logging, mining and many other purposes including extensive scientific research on tens of thousands of acres of land.

Pinchot, who would eventually start and serve as the first chief of the US Forest Service that now manages or conserves 193 million acres of forested and grass lands, prevailed overall. He had help, though. President Theodore Roosevelt agreed that conservation was the best practice for the majority of federally owned lands.

The adoption of the conservation model resulted in national forests being multi-billion dollar economic engines for hundreds of small towns and communities across America. If you like winter sports, there’s a good chance that your favorite ski run is on a national forest. The same goes for swimming, hiking and camping. And, there’s a good chance that the house you live in, and some of the furniture you sit on, was built by wood harvested from a national forest.

Another of Pinchot’s concepts from his wild lands conservation philosophies resulted in creation of the Forest Products Lab, the world’s preeminent wood research laboratory and a behemoth of technology and invention located in Madison, Wisconsin. Pinchot’s vision of managing forests for profit fit into his life mantra: The Greatest Good for the greatest number…”

But Pinchot’s success was not at the expense of John Muir’s preservation legacy aimed at permitting little to no industrial profit from the federal lands that have become our National Parks. In fact, Muir’s vision resulted in protecting forever some of the nation’s most iconic open spaces totaling over 100 million acres managed by an agency that was to be called the National Park Service.

Despite arguments by some, Muir’s preservation and Pinchot’s conservation philosophies are not at odds. In fact they play, together, a huge role in protecting our natural open spaces—for generations to come.

This “working together” philosophy of land management can perhaps best be seen by looking at a map of a large national park say Yellowstone or Yosemite or Shenandoah. You’ll notice that these parks (and many others) are connected to, or completely surround by, national forests or grasslands managed by the Forest Service.

For more than 100 years the success of the dual strategy of conservation and preservation has grown more and more obvious to the millions who benefit from jobs created and those who enjoy the wild places. Throughout the world other nations seek to emulate our federal land management system.

Thanks to Pinchot and Muir our federal dual system of conservation and preservation land management works in practical ways to keep our public lands open and productive.