“You can’t have a forest without a foundation of quality soil,” said Debbie Page-Dumroese, a soil scientist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station in Moscow, Idaho. That’s the lesson learned when hundreds of ponderosa pines were planted on rocky streambanks in national forests—only to die during their first year.

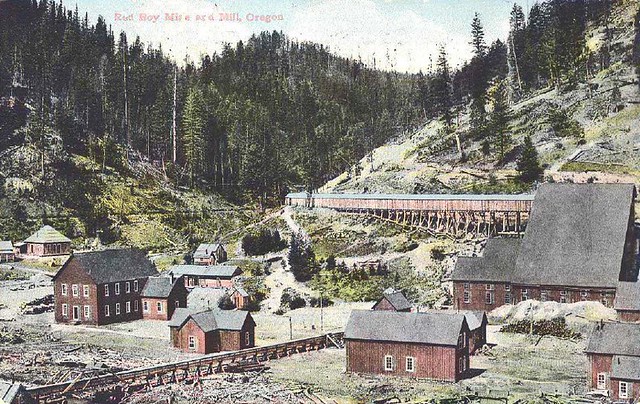

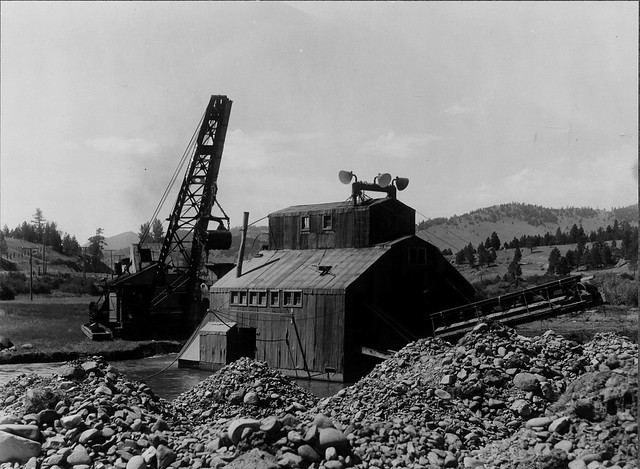

Rocky streambanks are a legacy of gold rush activities that began as early as the 1860s, when miners dredged streams and piled the rocks on the banks. Even near streams the rocky surface is inhospitable to trees, shrubs, even grasses. The hot dry environment in the Interior West only exacerbates growing conditions.

The ecological effects of abandoned mine sites are negative and long lasting. The sites have no vegetation to cool nearby streams or to block sedimentation from spilling into them. Local fish are impacted most directly, but anything or anyone who relies on a plentiful supply of cool, clean water downstream is also affected.

Page-Dumroese and her colleagues theorized it might be possibly to address the problem organically by building a thin layer of soil on top of the rocks.

“In a hot dry environment, it’s the quality of soil that matters, not the quantity,” she said.

She and her team combined biochar, wood chips, and biosolids from the Bend [Oregon] Water Reclamation facility to create an organic mantle on top of the rocky substrate for their experiment. Made from burning woody biomass into a charcoal product, biochar improves soil quality with carbon and helps it retain water during drought periods. The wood chips are from slash piles of dead branches, shrubs, and twigs created when forests are thinned to reduce excess fuel and lower fire danger. The biosolids contain numerous plant nutrients and can act as a fertilizer.

The researchers spread the organic material over a shallow soil cap atop rocks on an abandoned mine site. They seeded half the treated area with native grasses and planted tiny native grass plugs in the other half. Both sides flourished, and native forbs included in the mixture have popped up as well.

Grasses and forbs provide nutrients for grazing animals and, forbs also provide flowers for pollinators. As plants grow and die, they will add organic matter to the soil and provide a growing medium for larger plants, such as shrubs and trees.

This research could hand Forest Service and other land managers a simple way to restore degraded and barren land. Using organic amendments such as biochar and wood chips (PDF, 707 KB) also reduces the fire danger by turning excess forest fuel such as brush and dead branches into valuable organic commodities. It’s possible the revenue earned from these commodities could help pay for the labor to produce and spread them over degraded sites. Plus, excess biochar and wood chips could be sold to other markets, which could mean extra jobs for local communities.

“In the best-case scenario, it’s a win for the environment, a win for the agency, and a win for rural economies,” Page-Dumroese said.