The charismatic sage grouse is often in the spotlight as the flagship species in the sagebrush ecosystem. The smaller songbirds that live alongside the grouse don't always attract as much attention, but they are also good indicators of how the sagebrush range is faring.

Recently, in a project funded by the Sage Grouse Initiative (SGI), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and Intermountain West Joint Venture (IMJV), scientists set out to evaluate whether investments in sage grouse conservation serve as an “umbrella” that extends benefits to other sagebrush-dependent wildlife, too. These findings are summarized in a new Science to Solutions report by SGI, a partnership led by USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

We know from past SGI-funded research that easements put in place for sage grouse also doubled the protection of mule deer migration habitat and winter range, and that removing encroaching juniper to restore sage grouse habitat in Oregon increased the abundance of two sagebrush-loving songbirds by 50 to 80 percent.

Researchers Patrick Donnelly with IMJV and Jason Tack with University of Montana’s Avian Science Center used a trio of songbirds to further gauge the reach of the sage grouse umbrella across the West: the Brewer’s sparrow, sagebrush sparrow and sage thrasher. All three species have suffered from population declines due to the widespread loss and degradation of sagebrush habitats, and are identified as species of conservation concern by the FWS.

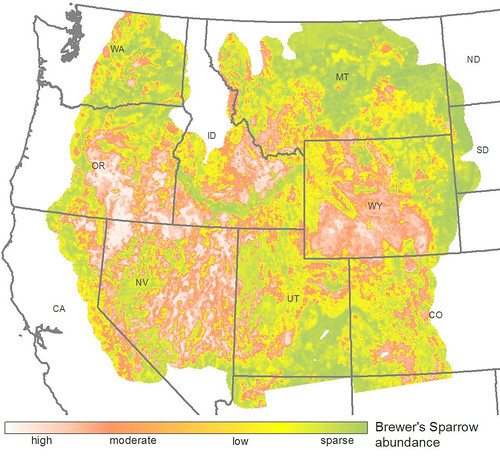

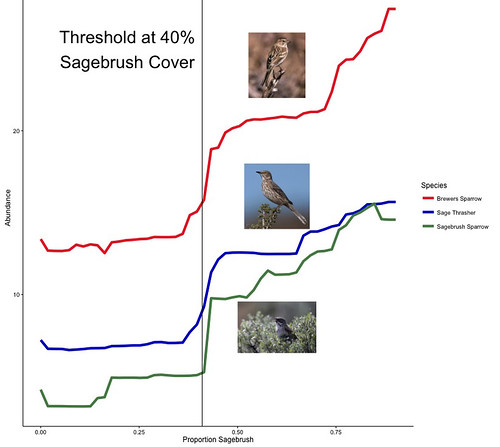

First, these researchers created abundance maps for each of the sagebrush songbirds using long-term bird count data coupled with measures of climate and habitat conditions. They found that the abundance of each songbird doubled when sagebrush covered 40 percent or more of the landscape. Unfortunately, they also discovered that fewer than 25 percent of sampled sites exceeded the 40 percent threshold of sagebrush-rich habitat.

Second, the scientists compared patterns of songbird abundance with the distribution of sage grouse leks, or mating grounds. Near large leks, which support 50 percent of known grouse populations, abundance was 15 percent higher for Brewer’s sparrow, 13 percent for sagebrush sparrow, and 19 percent for sage thrasher.

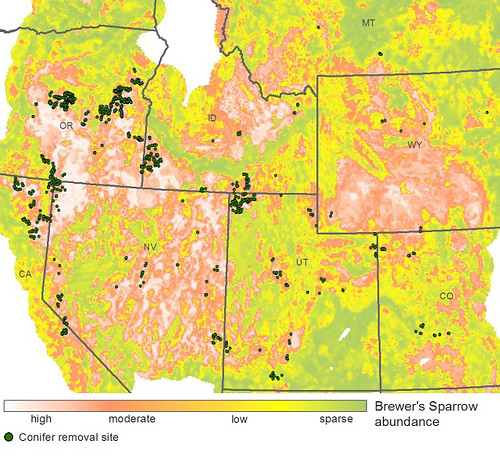

Third, they examined how sagebrush songbirds may benefit from sage grouse conservation actions taking place in 11 western states. Tack and Donnelly found that targeted conservation efforts for sage grouse also provide significant conservation benefits for these songbird species.

For instance, in the Great Basin, the maps revealed that 85 percent of conifer removal projects to restore sagebrush habitat overlapped with high abundance centers for Brewer’s sparrow. In drier reaches of sage grouse range, the scientists found that priority areas for managing weed invasions and wildfire (identified by the Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service) encompassed 51 percent of estimated sagebrush sparrow abundance and 55 percent of sage thrasher abundance.

In addition, the research showed that Wyoming’s land protection strategy for sage grouse also helps reduce habitat fragmentation for half of the state’s largest populations of sagebrush sparrow and sage thrasher.

These new songbird maps extend our understanding of how the sage grouse umbrella is working to benefit a host of other sagebrush wildlife, too. Plus, the maps will help partners, managers, and landowners target future conservation projects so that they generate the most return on investment for the sagebrush community as a whole.

Learn more about these findings by downloading this new report. This report is part of the Science to Solutions series offered through NRCS, SGI and the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative.